The fungus collections of the herbarium of the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe (KR)

Number of specimens and collection focus

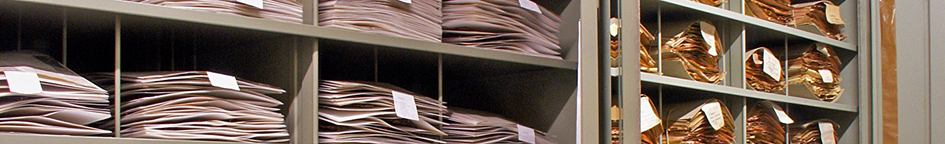

Since 2003, a fungus herbarium has been set up at the Karlsruhe Natural History Museum. Up to this point in time, the mycological collections, excluding lichens, only had around 11,800 specimens, stowed away in the attic of the main building of the museum, in a poor condition. The most important collection within these old holdings comes from the Wertheim teacher Wilhelm Stoll (1832-1917) with around 1,100 specimens. In the period that followed, the collection was expanded to around 111,000 specimens (as of December 2022) through donations, some purchases and current collections by the curator, museum employees and numerous other collectors, making it the largest mushroom collection in Baden-Württemberg. For reasons of space, the majority of the collections were relocated to premises on Fettweißstraße in Karlsruhe-Rheinhafen. Only the rust fungi remained in six cabinets in the Natural History Museum pavilion. The scientifically most important collections include: Wolfgang Brandenburger (microfungi parasitic on plants, especially rust fungi from Central Europe), Peter Döbbeler (rust fungi, Central America, Alps), Manfred Enderle (agarics, especially Conocybe, Psathyrella, southern Germany), Franz von Höhnel (non-agarics), Hanns Kreisel (macrofungi, especially puffballs, i.a. East Germany, Cuba), Lothar Krieglsteiner (macrofungi, southern Germany), Doris Laber (macrofungi, southern Black Forest), Helga Marxmüller (macrofungi with a focus on Russula and Armillaria, southern Germany, France including an important watercolor collection), Gusztáv von Moesz (parasitic microfungi, Hungary and Slovakia), Oskar Müller (rust fungi, Baden-Württemberg), Harald Ostrow (non-agarics southern Germany), Susanne Philippi (ascomycetes, Baden-Württemberg), Anke Schmidt (powdery mildew fungi, northern Germany), Martin Schnittler (slime molds, worldwide), Markus Scholler (all groups, especially rust fungi, Europe, USA), Leopold Schrimpl (macrofungi, Southern Black Forest), Horst Staub/Ursula Sauter (non-agarics, southwest Germany) and Wulfard Winterhoff (macrofungi, especially puffballs and agarics, Badenia). Furthermore, the historical collections of the University Herbarium Greifswald GFW (collections from the period 1810 to 1860 collected by Julius Münter and employees, Ludwig Rabenhorst, Franz Unger and others) were integrated into KR. In the preceeding years, new collections from the Black Forest National Park and the large Allgäuer Hochalpen nature reserve in Bavaria and the upper Rhine Valley are expected to be deposited in KR. Finally, there is a large number of exsiccatae. The focus of the collections is geographically on Central Europe (all groups of fungi) and taxonomically on rust fungi (Pucciniales), Puffballs (e.g. Bovista, Phallus, Tulostoma) and other non-agarics. In recent years, ectomycorrhizal fungi (including hypogaeous species) have been increasingly collected as part of secondary funding projects. There are particularly many collections from Baden-Württemberg, Bayern, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Nordrhein-Westfalen und Sachsen. The number of type specimens has not yet been fully evaluated and is currently 673.

In addition to the scientific evidence, there are also collections that are only used for exhibitions (display specimens), such as a collection of wax models of macrofungi.

For loans, please contact the curator: markus.scholler@smnk.de.

Exsiccatae

Fungus exsiccatae are published, uniformly designed, numbered sets of dried and preserved specimens with printed labels. They were usually made in several dozen duplicates and distributed worldwide. They are therefore also very important reference material, especially since the loss of a single document is less serious. It was not uncommon for exsiccate works to be published in bound book form. In publications, they are usually given in a standardized abbreviation, cf. the "Index of Exsiccatae" of the Botanische Staatssammlung München. Curators often incorporated exsiccatae in the general herbarium, as was the case in the Karlsruhe herbarium. The specimens from exsiccatae in the Karlsruhe General Herbarium are (mostly) incomplete collections, e.g. from the following Exsiccatae: California Fungi, Jack, Leiner & Stizenberger, Krypt. Badens, Marcucci, Unio Itin. Crypt., Mougeot & Nestler, Stirp. crypt. Vog.-Rhen. Rabenhorst, Klotzschii Herb. viv Mycol., Vanky, Ustil. Exs.. Still kept in separate cabinets and more or less complete are Brinkmann, Westf. Pilze, Neger, Forstschädl. Pilze, Jaap, Fungi Sel. Exs., Krieger, Fungi Saxon. Exs., Sydow & Sydow, Mycoth. Germ., Fuckel, Fungi Rhen. Exs., Zillig, Ustil. Eur., Briosi & Cavara, Fung. Paras. Piante Colt. Utili Ess., Krieger, Schädl. Pilze Kulturgew. und Schroeter, Pilze Schles.

The Database

More than half of the allout number of specimens have been digitized (as of December 2022) and can be viewed in simplified form in the Digital Catalogue of Fungi Digitaler Katalog (smnk.de)

Research with fungal herbaria

Public herbaria are collections of dried fungi and plants classified according to scientific criteria. All herbaria still have the function they had in Carl v. Linné's times in the 18th century: They serve to identify taxa, name, describe (taxonomy), and classify in a hierarchical system (systematics) and to determine the distribution area (chorology). They are also occasionally used for teaching and exhibitions, although not with the same importance as in earlier times. A modern research herbarium today has additional functions. First of all, there is biodiversity research and the study endangered species, mostly supported by powerful computer and database systems. With more detailed information on the individual, relationships between the species and their environment (ecology) can finally be established on the basis of collections. Furthermore, modern methods make it possible to isolate the smallest traces of e.g. heavy metals, proteins, DNA and environmental toxins from specimens of different age. In addition to taxonomists, who isolate the DNA and use its sequences to study taxonomic relationships, ecologists may strongly benefit from specimenss and new methods, e.g. in order to document environmental change. In comparison to the modern environmental specimen banks in Germany, which only allow the documentation of changes within the last decades, one can look back several centuries with the help of herbaria containing old specimens. Finally, external scientists may benefit from loaned specimens. In summary, one can say that herbaria are more important than ever for research. At the museum, the fungus herbarium is the basis for grant-funded research.

Curator in charge

Dr. Markus Scholler, Dipl.-Biol.

Phone: +49 721 175 2810

E-Mail: markus.scholler[at]smnk.de